In this article you will read about:

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) teaches a set of distress tolerance skills designed to help people get through intense emotional pain without making things worse. Alongside skills such as TIPP, Self-Soothe, and ACCEPTS, one of the core crisis-survival tools is the IMPROVE the Moment skill (Linehan, 2015).

The IMPROVE skill gives you a structured way to “improve the moment” when you can’t change the situation right now—but you can change how you move through it. It is beneficial for individuals living with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) or other conditions involving chronic emotion dysregulation, where crises can feel unbearable and impulsive urges are strong (Linehan, 1993; Mossini, 2024).

What Is the IMPROVE the Moment Skill in DBT?

In DBT, distress tolerance skills are grouped as crisis survival skills—short-term strategies to help you endure intense emotion safely when:

The situation is extremely painful.

You can’t change it quickly (or at all) in that moment.

Acting on impulsive urges would likely make things worse.

IMPROVE the Moment is one of these crisis survival skills. The acronym stands for:

I – Imagery

M – Meaning

P – Prayer (or spiritual connection)

R – Relaxation

O – One thing in the moment

V – Vacation

E – Encouragement (self-encouragement)

Each element is a small, concrete practice you can use to make a painful moment more bearable and support your nervous system in calming down (Linehan, 2015; Rathus & Miller, 2015).

Rather than trying to “fix” everything, IMPROVE helps you shift how you experience the moment, so you’re less likely to spiral into self-harm, substance use, explosive conflict, or other behaviors you’ll later regret (Neacsiu et al., 2010).

The IMPROVE Acronym: Distress Tolerance Skill Breakdown

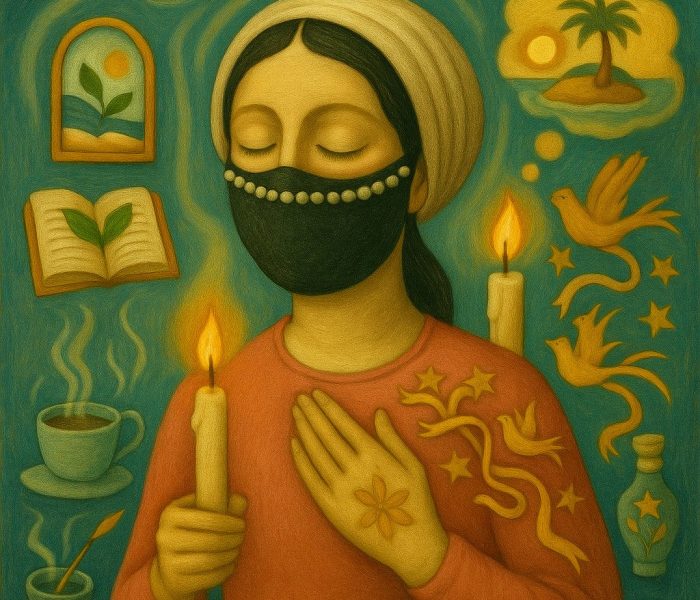

I – Imagery

Imagery uses the mind’s ability to imagine to create a brief inner refuge from distress. In DBT, clients are encouraged to:

Picture a safe place—a room, beach, forest, or spiritual space that feels secure.

Visualize getting through the crisis and later looking back with pride.

Imagine supportive figures (real, fictional, or symbolic) standing beside them.

This kind of guided imagery can reduce physiological arousal and support emotion regulation, particularly when practiced repeatedly (Linehan, 2015; Psychotherapy Academy, 2022).

M – Meaning

Meaning invites you to ask:

“Given that this pain is here, is there any meaning or purpose I can find in how I respond?”

Examples include:

Framing the moment as an opportunity to practice a new skill instead of repeating an old pattern.

Seeing suffering as part of a larger journey of growth, recovery, or spiritual development.

Remembering values (e.g., staying sober, being a caring parent, living authentically) and letting them shape your response.

Finding meaning doesn’t deny that something is unfair or painful; it simply asks, “How can I suffer less destructively?” Meaning-making has been linked with resilience and better adjustment to adversity in broader psychotherapy research (Fassbinder et al., 2016).

P – Prayer (or Spiritual Connection)

In the original DBT materials, Prayer refers to turning toward a sense of something larger than oneself—this might be God, a higher power, spiritual tradition, nature, or simply a sense of wise, transpersonal guidance (Linehan, 2015).

For spiritually oriented individuals, this could include:

Silent or spoken prayer.

Reading sacred texts or mantras.

Asking for strength, guidance, or acceptance.

For those who are not religious, this “P” can be reframed as “Practice Spirituality” or “Connect with Something Bigger”:

Feeling connected to nature, humanity, or collective struggle.

Reflecting on values or ideals that feel larger than immediate pain.

The aim is not to demand that distress disappears, but to lean into a sense of support and meaning beyond the self.

R – Relaxation

Relaxation focuses on deliberately calming the body, which in turn reduces the intensity of emotional experience. DBT suggests using:

Paced breathing (for example, longer exhales than inhales).

Progressive muscle relaxation, gently tensing and releasing muscle groups.

Warm baths, stretching, restorative yoga, or other soothing body practices.

Relaxation-based techniques have strong empirical support for reducing anxiety and physiological arousal, and are included across many evidence-based treatments (Kabat-Zinn, 2003; Positive Psychology, 2025).

O – One Thing in the Moment

“One thing in the moment” is a direct application of DBT mindfulness: one-mindfully doing just one thing, right now (Linehan, 2015).

Examples:

Focusing entirely on washing your hands—the feeling of water, temperature, movement.

Watching the flame of a candle with full attention.

Doing a simple task (folding laundry, making tea) without multitasking.

By narrowing the focus to a single, concrete action, the mind has less room to ruminate or catastrophize. This helps reduce emotional overwhelm and brings you back into the present moment.

V – Vacation

In DBT, Vacation doesn’t necessarily mean a week away—it often means a brief, intentional break from the stressor. This might involve:

Taking a few hours off from a draining task (while staying within your responsibilities).

Going to a library, park, or café for a short change of scene.

Creating a “mini-vacation” at home: a different room, a special chair, a short media break.

The key is permission: giving yourself a time-limited period where you are not actively solving the problem, but recovering enough to face it more effectively later (Rathus & Miller, 2015).

E – Encouragement (Self-Encouragement)

The final letter, Encouragement, is often described as self-cheerleading. DBT handouts include examples like:

“I can get through this.”

“This feeling will not last forever.”

“I’ve handled difficult things before.”

Self-directed, compassionate language can reduce shame and hopelessness, and is consistent with research on self-compassion as a buffer against emotional distress (Neacsiu et al., 2010; Lancastle et al., 2024).

Encouragement is not about pretending everything is fine; it’s about reminding yourself of your capacity to survive this moment without self-destruction.

Theoretical Foundations: IMPROVE Within DBT Distress Tolerance

Distress tolerance skills like IMPROVE are based on several key assumptions in DBT:

Pain is inevitable; suffering is optional. Trying to avoid or escape all pain is unrealistic and often leads to more suffering.

When you cannot change the situation immediately, your task is to get through the moment without making it worse.

Many clients lack effective crisis-survival strategies and instead rely on self-harm, substance use, or other high-risk behaviors to regulate emotion (Linehan, 1993, 2015).

IMPROVE offers a structured set of alternative behaviors to plug into this gap. Rather than acting impulsively when distress spikes, clients are coached to intentionally select one or more IMPROVE strategies and ride out the emotional wave.

Evidence supports this skills-based model: DBT skills use has been shown to mediate reductions in suicidal behavior, depression, and anger among individuals with BPD (Neacsiu et al., 2010). Systematic reviews of DBT skills training also point to improvements in emotion regulation, impulsivity, and self-harm when skills are practiced consistently (Mossini, 2024; Barnicot et al., 2016).

Practical Application: How to Use the IMPROVE Skill in Real Life

Think of IMPROVE the Moment as your “crisis playbook” when you can’t fix the situation right now, but you can influence how you move through it. Below is a structured way to turn the acronym into actual behavior.

Build Your Personal IMPROVE Menu

Before you’re in full crisis mode, take 10–15 minutes to create a custom list.

On a page or notes app, write IMPROVE vertically and fill in 2–4 ideas for each:

I – Imagery

Visualize a safe place (beach, forest, room).

Picture your future self looking back, proud you coped skillfully.

M – Meaning

“This is a chance to break an old pattern.”

“My suffering can fuel compassion—for myself and others.”

P – Prayer / Spiritual Connection

Short written or spoken prayer.

Reflect on something bigger than you: nature, humanity, values, purpose.

R – Relaxation

5–10 minutes of slow breathing.

Progressive muscle relaxation, gentle stretching, warm shower.

O – One Thing in the Moment

Make tea and focus fully on each step.

Fold laundry one item at a time, staying with the sensation.

V – Vacation

30–60 minutes off from problem-solving (movie, book, walk, café).

A “mental vacation”: time-limited break from thinking about the issue.

E – Encouragement

“This will pass; feelings are not forever.”

“I don’t have to like this to survive it.”

“Using skills is success, not perfection.”

Keep this list somewhere visible: journal, phone note, printed card.

A 20–30 Minute IMPROVE Routine for High Distress

Use this when your distress is around 7–10/10 and you notice strong urges to do something that would make things worse (self-harm, blow up at someone, binge, drink, etc.).

Step 1 – Name the Crisis (1 minute)

“I’m at a 9/10 and my urge is to __.”

Commit: “For the next 20–30 minutes, I will only use skills, not act on urges.”

Step 2 – Pick 3–4 Letters from IMPROVE (15–20 minutes)

Example combo: I + R + O + E

Imagery (5 minutes)

Close your eyes and walk through your safe place in detail: sights, sounds, temperature, smells.Relaxation (5–10 minutes)

Do paced breathing (inhale 4, exhale 6) or tense–release each muscle group from feet to face.One Thing in the Moment (5 minutes)

Choose a simple task—washing a dish, making a drink, brushing your hair—and do it one-mindfully, returning your attention every time it drifts.Encouragement (1–2 minutes)

Speak or write a few phrases:“I’ve survived intense feelings before.”

“Right now my job is to get through this moment safely.”

(You can swap in Meaning, Vacation, or Prayer depending on the situation and what resonates.)

Step 3 – Recheck Your Distress (2 minutes)

Re-rate your distress from 0–10.

Even a drop from 9 to 7 is real progress; it gives more room for Wise Mind choices.

Step 4 – Choose the Next Wise-Mind Step

Ask:

“What’s the most effective thing I can do now?”

Options might be: use another DBT skill, rest, reach out to someone safe, or schedule time later to problem-solve the situation.

Daily “Micro-Practice” to Make IMPROVE Automatic

The more you practice IMPROVE outside of intense crises, the easier it is to access when everything is on fire.

Try this micro-practice once a day:

Pick one letter of IMPROVE.

Use that skill for 3–5 minutes during mild stress (annoyance, worry, tension).

Briefly note: “What did I try? Did my mood shift at all?”

Over a few weeks, you’ll start to build a reflex: when distress spikes, your brain is already familiar with Imagery, Relaxation, Encouragement, etc. and they’ll feel less forced or awkward.

Empirical Support for IMPROVE and Distress Tolerance Skills

Direct research on IMPROVE specifically is limited, as most studies evaluate DBT skills modules as a package rather than individual acronyms. However, several lines of evidence support the use of distress tolerance strategies like IMPROVE:

Skills use as a mechanism of change: In a landmark study, Neacsiu et al. (2010) found that increases in overall DBT skills use mediated reductions in suicidal behavior, depression, and anger among individuals with BPD.

DBT skills training outcomes: Reviews of DBT skills training (with modules including distress tolerance) show improvements in emotion dysregulation, self-harm, mood symptoms, and impulsivity across diagnostic groups (Mossini, 2024; Barnicot et al., 2016).

Distress tolerance as a target: Distress tolerance has been identified as a key mechanism for reducing maladaptive coping in mood and personality disorders, with DBT often cited as a primary evidence-based approach for strengthening this capacity (Lancastle et al., 2024; Eat Breathe Thrive, 2025).

Taken together, these findings support the clinical intuition that skills like IMPROVE—when used consistently—contribute to greater emotional stability and reduced reliance on crisis behaviors.

Limitations and Clinical Considerations

As with all DBT skills, IMPROVE is powerful but not all-purpose. Some important considerations:

Short-term tool, not a full solution.

IMPROVE is meant to help you get through the moment—it does not replace trauma work, problem-solving, or structural change when those are needed.Risk of avoidance.

If used excessively, “Vacation” or “Imagery” could become ways to avoid necessary action. Therapists must emphasize that IMPROVE is for crisis survival, not permanent withdrawal.Cultural and spiritual sensitivity.

The “Prayer” component must be adapted to fit the client’s beliefs and background; some will resonate with spiritual practices, others with nature or values-based reflection.Access and environment.

Not every component is feasible in every setting (e.g., inpatient units, workplaces). Creative adaptation is often required—imagery and breathing are usually available anywhere.

When integrated thoughtfully into a full DBT program, IMPROVE becomes one of several interlocking skills that together support a life worth living, even in the presence of ongoing stress or pain (Linehan, 2015; McLean Hospital, 2024).

Conclusion

The IMPROVE the Moment skill in DBT is a structured, evidence-informed way to make unbearable moments more survivable. By drawing on Imagery, Meaning, Prayer/Spiritual connection, Relaxation, One thing in the moment, Vacation, and Encouragement, individuals can shift how they relate to distress—even when they cannot immediately change the situation itself.

For people living with BPD or other forms of severe emotional dysregulation, IMPROVE offers more than a clever acronym. It is a practical, repeatable roadmap for staying alive, aligned with values, and open to growth during some of life’s hardest moments. Used alongside other DBT skills and professional support, IMPROVE helps transform “I can’t stand this” into “This is hard, but I can get through it—one skill, one moment at a time.”

FAQ

Most frequent questions and answers about the IMPROVE the Moment Skills in DBT

Think of them as different tools for different “intensity levels” and needs:

TIPP (Temperature, Intense exercise, Paced breathing, Progressive relaxation) is best for very high physiological arousal—panic, rage, full-body anxiety.

ACCEPTS is great when you need distraction to ride out urges.

IMPROVE is ideal when you can’t change the situation right now, but want to make the experience of the moment more bearable and meaningful.

In real life, you might use TIPP first to calm your body, then IMPROVE and ACCEPTS to get through the rest of the day.

No. IMPROVE is a menu, not a checklist. You do not need to hit all seven components.

In a given situation, 2–4 letters is usually enough.

Over time, you’ll discover your “go-to combos” (e.g., Imagery + Relaxation + Encouragement).

The goal is effectiveness, not perfection: choose what works for this moment.

Totally fine. “P” is often re-framed as “spiritual connection” or “connecting with something bigger than yourself.” That can look like:

Reflecting on your values or purpose (“Why do I want to stay alive/healthy today?”).

Feeling connected to nature, humanity, or a cause.

Tapping into a sense of “Wise Mind” or inner wisdom rather than a deity.

If none of that feels right, you can simply skip P and lean more on the other letters.

That doesn’t mean you failed or the skill is useless. A few important points:

Sometimes distress only drops a little—say, from 9/10 to 7/10. That’s still valuable space.

You may need to stack skills (e.g., TIPP + IMPROVE + Self-Soothe) or repeat a second round.

If urges stay strong or get worse, it’s a sign you may need extra support, such as:

Reaching out to a trusted person

Contacting your therapist or treatment team

Using crisis or emergency resources if you’re at risk of acting on urges

IMPROVE is meant to help, but it’s not a replacement for professional support when you’re unsafe.

No. IMPROVE is a skill, not a full treatment.

It can support therapy and, in some cases, make medication more effective by reducing crisis behaviors and improving emotion regulation.

It does not address underlying trauma, long-term patterns, or biological vulnerabilities on its own.

Decisions about therapy and medication should always be made with a qualified mental health professional. IMPROVE is best used as one piece of a broader DBT or mental health plan, not a standalone solution.

IMPROVE the Moment Skills in DBT Book Recommendations

Here is a collection of the best books on the market related to IMPROVE the Moment DBT Skills:

Our commitment to you

Our team takes pride in crafting informative and well-researched articles and resources for our readers.

We believe in making academic writing accessible and engaging for everyone, which is why we take great care in curating only the most reliable and verifiable sources of knowledge. By presenting complex concepts in a simplified and concise manner, we hope to make learning an enjoyable experience that can leave a lasting impact on our readers.

Additionally, we strive to make our articles visually appealing and aesthetically pleasing, using different design elements and techniques to enhance the reader’s experience. We firmly believe that the way in which information is presented can have a significant impact on how well it is understood and retained, and we take this responsibility seriously.

Click on the icon to see all your thoughts in the Dashboard.

Your Thoughts about IMPROVE the Moment Skills in DBT

It’s highly recommended that you jot down any ideas or reflections that come to mind regarding IMPROVE the Moment Skills in DBT, including related behaviours, emotions, situations, or other associations you may make. This way, you can refer back to them on your Dashboard or Reflect pop-ups, compare them with your current behaviours, and make any necessary adjustments to keep evolving. Learn more about this feature and how it can benefit you.

References

- Barnicot, K., et al. (2016). Skills use and common treatment processes in dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 52, 147–156.

- DialecticalBehaviorTherapy.com. (2024). Dialectical behavior therapy: DBT skills, worksheets, videos.

- Eat Breathe Thrive. (2025). What is distress tolerance? RO DBT skills for emotional resilience.

- Fassbinder, E., et al. (2016). Emotion regulation in schema therapy and dialectical behavior therapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1373.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156.

- Lancastle, D., et al. (2024). A systematic review of interventions aimed at improving distress tolerance. Current Opinion in Psychology, 56, 101746.

- Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press.

- Linehan, M. M. (2015). DBT® skills training manual (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Linehan, M. M. (2015). DBT® skills training handouts and worksheets (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- McLean Hospital. (2024). Practical DBT strategies & techniques.

- Mossini, M. (2024). Efficacy of dialectical behavioral therapy skills in addressing emotional dysregulation among adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 13, 174.

- Neacsiu, A. D., Rizvi, S. L., & Linehan, M. M. (2010). Dialectical behavior therapy skills use as a mediator and outcome of treatment for borderline personality disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(9), 832–839.

- Psychotherapy Academy. (2022). Distress tolerance skills in DBT trauma work: IMPROVE the moment, RAIN dance and HALT.

- Rathus, J. H., & Miller, A. L. (2015). DBT® skills manual for adolescents. Guilford Press.

- PositivePsychology.com. (2025). Emotional regulation: 5 evidence-based skills and strategies.